The Soul Tigers current storage space inside I.S. 292. The Soul Tigers might lose their practice space next year due to the expansion of the UFT Charter School co-located inside the building. Photo By: Jeanette D. Moses

EAST NEW YORK, Brooklyn — Mayor Michael Bloomberg will be known as the metrics mayor: the businessman who used analytics to revive a city reeling from 9/11. With numbers on his side, he implemented a massive 311 system, tracked crime statistics and supported his public health initiatives. In 2011, he tweeted, “In God we trust. Everyone else, bring data.”

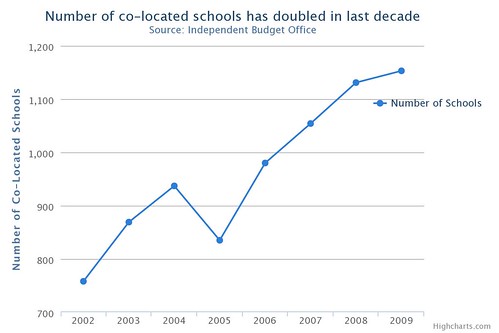

However, there are some sectors, like education, where many say that using data has fallen short of solving certain problems. Bloomberg intensified a policy of chopping up larger schools, closing others and co-locating multiple schools within the same building. Although the policy began before Bloomberg, his goal was to create smaller class sizes and better utilize available space in a crowded city. In the last ten years, about 96 schools have closed and 656 new schools have opened, according to the Independent Budget Office and the Mayor’s Office. As of the 2009-2010 school year, 39 percent of the city’s school buildings were overcrowded, up from 37 percent in 2005-2006. On average, co-located buildings are less crowded than buildings with just one school in them, according to the budget office.

“We’ve opened more schools so that students can take full advantage of the educational opportunities available through public education,” said Schools Chancellor Dennis M. Walcott as he announced at a press conference in April that 78 new schools will open in the fall. “Teachers see it, parents say it and data show it: our graduation rates are higher, the achievement gap is closing.”

Video: Stories of Co-Location

The Soul Tigers Marching Band may lose their practice space inside I.S. 292, because of the expansion of a UFT Charter School.

True to its original plan, the Bloomberg administration has chosen severely underutilized buildings to co-locate and those schools are still under capacity, on average. But some believe these facts don’t reflect the reality. They say the numbers are detached from the experience on the ground, where schools struggle to come up with fair and efficient ways of sharing space, particularly as schools phase in and out of a building as new schools open or existing schools close. Arguments arise over the use of resources, such as who will use lunchrooms when, and how to divvy up classrooms and designate hallway use.

Some public schools advocates claim that the Bloomberg administration unfairly favors charters, who often don’t pay rent to the city, and that charter schools seem to get first dibs on space. However, this is not uniformly true. More often, the very nature of sharing a space in a building causes friction, even at buildings that haven’t reached capacity.

“Being squashed in that small space does cause a lot of tension,” said Sandra Lawrence, whose child attends a charter middle school in Bedford-Stuyvesant that is co-located with a public elementary school inside P.S. 256. “Charter schools are public schools, so you should technically be able to have a reasonable kind of agreement.”

-Sandra Lawrence, charter school parent.

The schools are currently quibbling over much-needed space, which Lawrence has experienced first-hand. The problem in the building, P.S. 256, is that space is awkwardly distributed. The charter middle school currently occupies one half of one floor while the public elementary school occupies three and a half floors of the building.

How does this play out during the year? Lawrence has seen charter school students take the state-administered common core tests in the hallways since there is not enough space. Lawrence also thinks that charter schools with larger networks are able to get better arrangements than the smaller ones, like hers.

Though the details vary, when two or more schools share a building, conflict and tension results.

Number of Co-Located Schools Doubles Under Bloomberg

Co-located schools existed when Bloomberg took office, but his administration intensified the policy.

Co-Located Schools in New York City

The Bloomberg administration opened 656 new schools in the last ten years, as an attempt to limit crowding, provide smaller class sizes and better utilize limited space. Buildings with just one school in them are not represented in this map.

For example, in one building in East New York, Brooklyn, the students do not end up using the space as they are supposed to. The UFT Charter High School inside I.S.166 shares space with the district middle school, George Gershwin Jr. High. Students from each school have designated entrances and stairwells, in part to keep the age groups separated. But according to one parent, the space division isn’t seamless and the students from both schools regularly pass each other in the hallways.

“It’s a bit much to have 11 year olds around these 16, 17, 18 year old kids,” said Gregory Grant, a parent of three children who attend George Gershwin. “At this high school age, everyone has a boyfriend, girlfriend, and you’ll see them walking around the school, holding hands. All types of stuff that these kids shouldn’t be privy to at this age.”

According to the NYC Department of Education, next year this building will house two additional schools: Achievement First Charter High School 2 and a new district middle school. This will put four schools in one space—a move that Grant says doesn’t make sense. When the charter school first came into the building the principal had to fight to keep the public school students eating lunch near lunchtime instead of at 10 a.m., which is the first lunch period of the day. However, pushing lunch to the end of the day produced other problems.

“Now by the time our kids get down to the lunchroom it’s an absolute mess. Our kids are sitting and eating in filth,” said Grant. He worries what the space utilization will look like next year when four schools share areas like the cafeteria.

Charter and public schools fight for resources

Co-location, particularly with a public and a charter school, has caused many problems. Some parents feel as if the schools are pitted against each other, battling for available resources, from classrooms to the best times to use shared spaces. At I.S. 166, for example, one group of students eats lunch early in the morning and others late in the afternoon. At I.S. 292 the Soul Tigers, a marching band with students from multiple area schools, may be forced out of their practice space to make room for an expanding UFT Charter School.

“Anytime you’re taking space it’s an issue,” said Kenyatte Hughes, director of the Soul Tigers Marching Band. If they can’t reach an agreement with the UFT Charter School, Hughes will have to look for another practice space that can accommodate the 250 band members.

“The kids won’t have a music program anymore because we would have to leave the school if worse came to worse.”

Because of situations like this, some parents are suspicious of co-location. Muba Yarofulani, a parent in Canarsie and the co-president of the Campaign for Public Education, said families in her district feel that the Bloomberg administration gives preference to charters at the expense of public schools.

This suspicion isn’t completely unfounded, said David Bloomfield, an education policy professor at the CUNY Graduate Center and Brooklyn College.

“There is no question that the Bloomberg administration has favored charter schools over traditional public schools. Period,” he said, mainly by letting them occupy public school buildings rent-free.

The mayor favors the entrepreneurial nature of charter schools, said Bloomfield. Another reason the mayor may support charters comes down to money. Pension costs for Department of Education employees have gone up nearly 370 percent since 2002, to $2.9 billion a year, for example. But Bloomfield notes that the city does not have to pay charter teachers’ pensions.

In addition, if the schools have very different resources it causes a rift between students and an often-unseen emotional cost, parents and educators say.

In Canarsie at P.S. 114, Yarofulani said students who attend the charter school have remodeled classrooms with laptops and smart boards, which is not the case for the public school children. The kids are more than aware of this fact, she explained.

“When we have students on one floor that are struggling to even have the right materials, there are students who are boasting about the things that they have,” said Yarofulani. “It automatically brings a friction between students. It makes one feel less than the other.”

Joseph Viteritti, who teaches public policy at Hunter College and directed the commission to determine whether mayoral control of schools should continue, supports charter schools and believes in having more choices for parents and kids. However, the way charters are being introduced into existing school buildings is problematic, he said, and sets up an atmosphere of competition. Public school parents often resent having to share space, putting amicable compromise farther out of reach.

“You can’t force things. Schools are crowded to begin with. When you put a school in the same building and take space and reallocated to a charter, it’s not a great way,” Viteritti said.

The solution, he said, is better collaboration, but that’s only a part of it. “I think there is a larger policy problem. There needs to be a source of funding [for charter schools] so they have space.”

In Canarsie, Yarofulani said that if charter schools and public schools continue to be co-located the relationship between them will have to become more cooperative.

“[The charter] shouldn’t be there to compete, it should be there to assist. To make things better, not to make a division,” she said. “We should find ways to work together instead of trying to say one is better than the other.”